Ireland, Part 3

Ireland has a ghostly reputation; there are reasons for that.

Note: This is an ongoing series. We recommend you read Part 1 and Part 2 before proceeding with this week’s installment.

Ireland’s a land filled with ghosts, as the locals will be the first to tell you. Influential Irish ghost story writers such as J. Sheridan Le Fanu and Bram Stoker (author of Dracula!) help cement the Emerald Isle’s reputation as a haven for specters, but there’s more to it than that.

It starts with the landscape. Take a long, slow drive (there is no other kind) up and around Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way and you’ll get a glimpse of the surroundings that have helped shape Ireland’s affinity for the uncanny.

It seems strange to say, given the island is only about 170 miles wide and 301 miles from top to bottom, but the western coast presents a remoteness that is almost otherworldly, a land of grays and greens and browns with far more sheep (haphazardly sprayed with specific colors identifying their ownership) than people. Roads are narrow, constricting to one lane in some places, contributing to the feeling of isolation as your vehicle creeps along. A ten mile drive isn’t just 10 miles in on the Wild Atlantic Way; it’s an odyssey that will end “sometime later.”

It seems strange to say, given the island is only about 170 miles wide and 301 miles from top to bottom, but the western coast presents a remoteness that is almost otherworldly, a land of grays and greens and browns with far more sheep (haphazardly sprayed with specific colors identifying their ownership) than people. Roads are narrow, constricting to one lane in some places, contributing to the feeling of isolation as your vehicle creeps along. A ten mile drive isn’t just 10 miles in on the Wild Atlantic Way; it’s an odyssey that will end “sometime later.”

Rolling green hills rise up on each side of you, just inches from the edge of the road, massive barriers blocking access to a more civilized world, which seems very far away. Bogs—wetlands composed mostly of peat—are massive and plentiful. If the low gray sky and the encroaching mountains don’t make you feel like nature’s about to swallow you up, the soft ground below you just might.

Rolling green hills rise up on each side of you, just inches from the edge of the road, massive barriers blocking access to a more civilized world, which seems very far away. Bogs—wetlands composed mostly of peat—are massive and plentiful. If the low gray sky and the encroaching mountains don’t make you feel like nature’s about to swallow you up, the soft ground below you just might.

When you do come across a town in these parts, it’s mirage-like, an oasis in reverse, with encroaching gloom instead of burning desert sands responsible for the illusion. Frankly, it was hard to imagine how the denizens of these hamlets might go about their daily errands without the niceties of modern civilization, but we had to admit such circumstances held a certain amount of appeal. Leenane Village on Ireland’s only fjord, Killary Harbour, is a good example of what we mean:

*** Convenience Store Alert ***

If you thought we didn’t see many convenience stores and gas stations during this drive, you’d be right, but we passed by one in the tiny town of Moycullen (an absolute metropolis in contrast to surrounding “population centers”). While the majority of our group visited the Connemara Marble Visitor Center and Manufacturing Facility, we were in the middle of the street taking this photo. Note the attached carpet and upholstery store, the cozy apartment on the second floor, and impressive “phoenix” logo. The c-store brand is Spar, which from our observations is one of the biggest in Ireland. Some Spars we found were convenience store palaces, like the one in Dublin. This one is a little homier.

*** End Convenience Store Alert ***

While the landscape surely sets an ethereal tone, in truth it is only a reflection of the mystical spirit of the Irish people that has been forged over centuries, probably longer than that. If the ghosts of the past seem to cling to the west, we shouldn’t forget that this is the part of the country that was heaviest hit by the Irish potato famine that started in 1845 and touched off the flight of hundreds of thousands to the U.S. Across the island from the bustling metropolises of Dublin and Belfast, and rife with boglands less than ideal for agriculture, this is where the rural poor lived, farming potatoes as their main source of nourishment. This tragic legacy is woven into the culture of the Wild Atlantic Way, where the toughness and resilience of the Irish people is not mourned, but celebrated, albeit soberly. The somber beauty of the National Famine Memorial reflects this part of the Irish character:

One of the more mysterious results of the famine is the Deserted Village at Slievemore on Achill Island. Ireland’s largest island, an outlier on the Atlantic Ocean, is as remote as anything on the Wild Atlantic Way. About 57 square miles in size with 2,500 or so full time residents, it is home to a rather low key RV camp and a small town center consisting mostly of a pub, restaurant/store, and lodging. The remains of close to 100 stone cottages stand here, that were once seasonal residences for unknown tenants. The structures were abandoned during the famine due to rent increases and less than favorable farming land. Older artifacts, some close to 5,000 years in age, can also be found at the site. It’s quiet, reflective, and a little unnerving. When the wind calms, you might even think you’re hearing whispers.

One of the more mysterious results of the famine is the Deserted Village at Slievemore on Achill Island. Ireland’s largest island, an outlier on the Atlantic Ocean, is as remote as anything on the Wild Atlantic Way. About 57 square miles in size with 2,500 or so full time residents, it is home to a rather low key RV camp and a small town center consisting mostly of a pub, restaurant/store, and lodging. The remains of close to 100 stone cottages stand here, that were once seasonal residences for unknown tenants. The structures were abandoned during the famine due to rent increases and less than favorable farming land. Older artifacts, some close to 5,000 years in age, can also be found at the site. It’s quiet, reflective, and a little unnerving. When the wind calms, you might even think you’re hearing whispers.

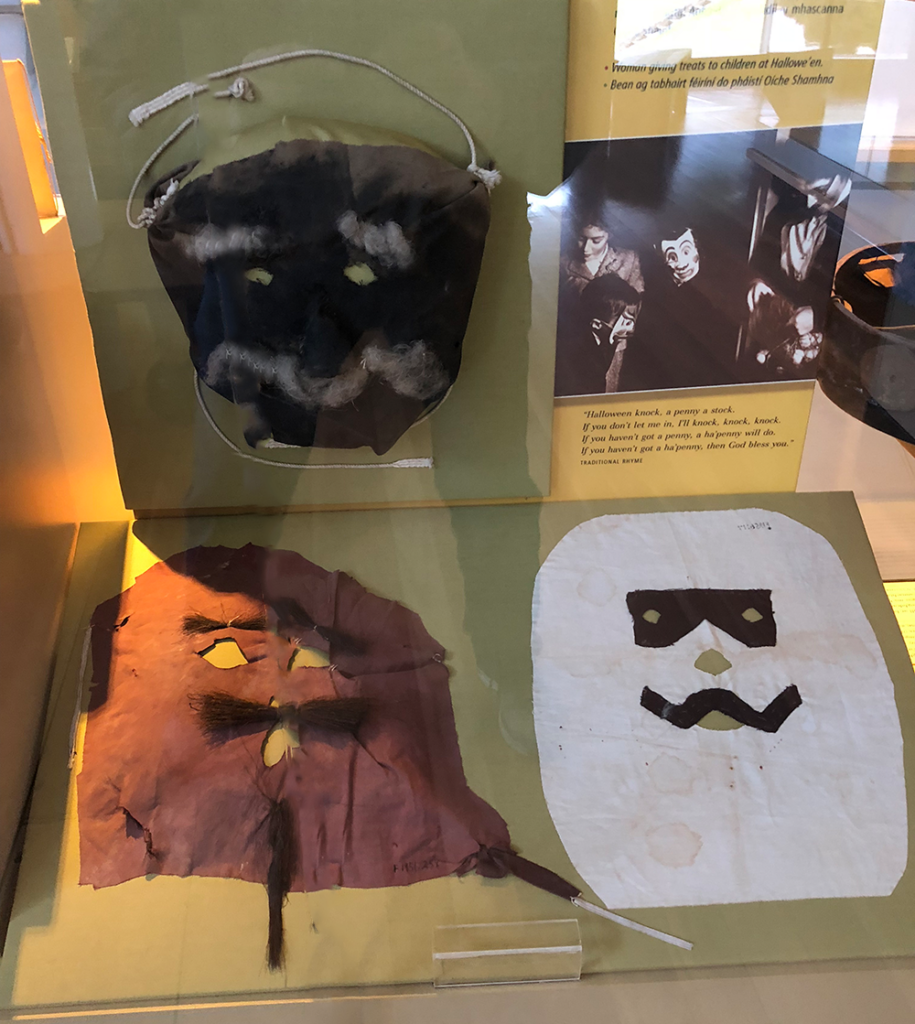

A closer, more personal look at the daily existence of mid-19th century Irish country folk can be found at the National Museum of Ireland – Country Life. Attractive and thoroughly modern, the museum is filled with exhibits recreating the daily activities of their hardscrabble lives, an existence that will certainly make one think twice before complaining about the difficulties of modern life. A rich vein of folklore runs through Irish culture, with deep roots in the myth and superstition that informs the area. This is, after all, basically the birthplace of Halloween, which the museum recognizes with a creepy collection of prototypical Halloween masks circa 1850.

A closer, more personal look at the daily existence of mid-19th century Irish country folk can be found at the National Museum of Ireland – Country Life. Attractive and thoroughly modern, the museum is filled with exhibits recreating the daily activities of their hardscrabble lives, an existence that will certainly make one think twice before complaining about the difficulties of modern life. A rich vein of folklore runs through Irish culture, with deep roots in the myth and superstition that informs the area. This is, after all, basically the birthplace of Halloween, which the museum recognizes with a creepy collection of prototypical Halloween masks circa 1850.

As the Irish of this time and place did not have access to a lot of natural resources, they became quite handy with wicker, a technique for making things from woven willow tree materials, which were plentiful. While most of us are familiar with wicker baskets, the Irish made everything out of it, including chairs, boats, and weapons. They made statues out of it, as well, and—true to this post’s theme—it’s almost impossible to look at these without conjuring up visions of dark Celtic otherworldliness, even if you haven’t watched The Wicker Man. Examples rise at various locations throughout the museum grounds. The genial fellow pictured below celebrates the Irish farmer, and is pretty typical of this kind of folk art.

As the Irish of this time and place did not have access to a lot of natural resources, they became quite handy with wicker, a technique for making things from woven willow tree materials, which were plentiful. While most of us are familiar with wicker baskets, the Irish made everything out of it, including chairs, boats, and weapons. They made statues out of it, as well, and—true to this post’s theme—it’s almost impossible to look at these without conjuring up visions of dark Celtic otherworldliness, even if you haven’t watched The Wicker Man. Examples rise at various locations throughout the museum grounds. The genial fellow pictured below celebrates the Irish farmer, and is pretty typical of this kind of folk art.

Rural Ireland is also home to the Travellers, an Irish itinerant ethnic group, sometimes pejoratively referred to as gypsies. Like the more well-known Eastern European Romani, the travellers used wagons as transportation, and in some cases, living quarters. A colorful example stands outside the Museum of Country Life:

Rural Ireland is also home to the Travellers, an Irish itinerant ethnic group, sometimes pejoratively referred to as gypsies. Like the more well-known Eastern European Romani, the travellers used wagons as transportation, and in some cases, living quarters. A colorful example stands outside the Museum of Country Life:

The impressive original museum structure stands in front of the property. It does look a bit like it might be haunted, doesn’t it?

The impressive original museum structure stands in front of the property. It does look a bit like it might be haunted, doesn’t it?

The mystical side of Ireland’s culture gives it a singular appeal that underlies other aspects of the country’s personality. It runs centuries deep and makes for an unforgettable visit. The more populated areas are lots of fun and full of interesting attractions—including convenience stores—but there’s nothing quite like Ireland’s wild west. See you next week.

The mystical side of Ireland’s culture gives it a singular appeal that underlies other aspects of the country’s personality. It runs centuries deep and makes for an unforgettable visit. The more populated areas are lots of fun and full of interesting attractions—including convenience stores—but there’s nothing quite like Ireland’s wild west. See you next week.

Click here to go to Part 4 of this series.

Leave A Comment